Nanotextures solve a historic problem

Nanotexturing that prevents scale forming on the inside of pipes can reduce plant maintenance costs significantly

A team of researchers from the laboratories of Harvard and the Wyss Institute in the USA have joined forces to develop an extremely adhesive bio-glue for medical use, inspired by slugs.

In spite of the relentless technification of human society, Nature is still the greatest source of inspiration when facing new challenges. Some time ago, the seed of the burdock burr gave us the key to Velcro manufacturing while sharks gave us a master class on hydrodynamic swimsuit designing, to name a few. Our latest muse is a creature that, usually, is not considered as the embodiment of beauty and harmony. We are talking about the Arion subfuscus, a simple slug which is a common dweller in many European gardens. What was the initial issue? The lack of adhesiveness of conventional glues over damp human tissues, in addition to their toxicity, suggested the development of more efficient alternatives regarding wound healing.

A team of scientists from the Weyss Institute in collaboration with Harvard´s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences noticed that slugs, when under stressful conditions, released an extremely sticky mucus capable of keeping them firmly attached to almost any type of surface, even when wet. Dr. Jianyu Li, first contributor to the article published in Science magazine describing the findings, realized that the substance excreted by slugs contained a matrix of positively charged proteins, capable of generating an electrostatic attraction to surfaces featuring negatively charged particles. On top of that, adhesion is ensured through covalent bonds and physical interpenetration caused by the fluid.

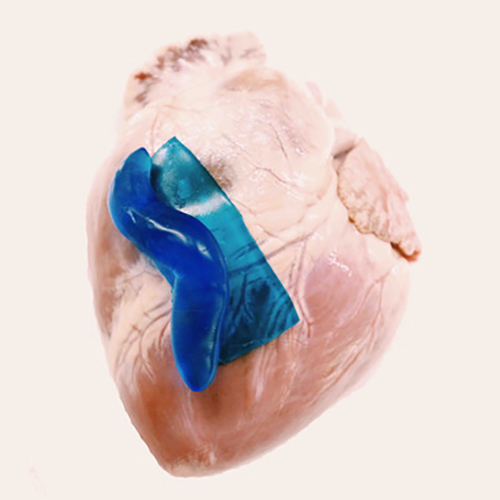

After exploring these properties, they developed a blue hydrogel (the darker, the thicker) which, in addition to providing an adhesive capability three times higher than those components being used in Medicine up until now, introduced a previously unheard of element. “The key feature of our material is the combination of a very strong adhesive force and the ability to transfer and dissipate stress, which have historically not been integrated into a single adhesive”, highlights Dave Mooney, another of the proponents. This property is achieved when bonds between calcium atoms and hydrogel are broken, thus dissipating the energy when the material is under stress and providing it with higher resistance to torsion.

The resulting bio-glue has been successfully tested on a variety of pig tissues –such as skin, cartilage, liver and artery–, both wet and dry. The team has even used it to seal a hole in a pig heart. “The glue adheres to a surface within three minutes, but then gets stronger. Within half an hour it is as strong as the body's own cartilage”, Dr. Lin stated. Tests carried out on rats demonstrated that the adhesive maintained its stability and bonding for weeks. Right now, they’re working on versions of the adhesive out of biodegradable materials, as well as on techniques to implement mass production.

The glue developed by Lin and his team trails some other medical adhesives like the one devised by Gecko Biomedical, inspired in the mucous secretions of marine worms. This bio-glue is currently at test stage and could become another alternative to classic stitches.

This bio-glue based on the fluids of slugs and worms belongs to a discipline called biomimicry that has led to many discoveries and inventions. It consists, essentially, in applying techniques learned from Nature under the motto of emulation, not duplication, while drawing inspiration from its underlying principles. Biomimicry can operate at diverse levels, from a purely aesthetic or structural approach to implications in the cell functioning of an organism. Mercedes-Benz, for instance, took inspiration from a fish species –the famous yellow boxfish starring in Finding Nemo – to design a vehicle with optimum aerodynamic qualities.

Sources: BBC, Science, Wyss Institute, Wired

All fields are mandatory.

Read the most discussed articles

{{CommentsCount}} Comments

Currently no one has commented on the news.

Be the first to leave a comment.

{{firstLevelComment.Name}}

{{firstLevelComment.DaysAgo}} days ago

{{firstLevelComment.Text}}

Answer{{secondLevelComment.Name}}

{{secondLevelComment.DaysAgo}} days ago

{{secondLevelComment.Text}}